DeepDive: How mining became Canada’s surprising new engine of economic growth

DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of Centre for Civic Engagement.

Mining is an increasingly rare success story in Canada’s economy. While most public commentary focuses on the economic threat from Donald Trump, Canada’s chronic slow economic growth, and stagnant exports, mining’s buoyancy is a reminder that Canada still can be a beacon for investment and successfully compete in global markets as well as a strategic industry in an era of economic and geopolitical competition.

This DeepDive essay provides an overview of recent developments in Canada’s mining industry.This paper focuses on the extraction of metal ores and non-metallic minerals, which excludes oil and gas. Some classifications of metals and minerals (especially export data) include products that have been smelted and refined. It documents mining’s expanding output, incomes, and jobs, fuelled by the recent surge of investments and export demand for most metals and minerals.

The resurgence of the mining industry’s fortunes over the last two decades is a remarkable turnaround. Canada’s mining industry contracted steadily in the 1990s, with output receding at a time of slumping demand and prices on world markets while investment plunged so low that mining’s capital stock fell outright.Output fell 13.5 percent and the capital stock shrank 23 percent in the 1990s. With output and investment falling, it is not surprising that mining employment also declined during the 1990s. Many analysts thought all these negative trends were a harbinger of mining ceding its place among Canada’s growth industries.

Instead, mining’s doldrums of the 1990s have been followed by two decades of spectacular growth. Record high prices on global markets have lifted exports, investment, and employment to their highest levels ever. Metals and mining are now Canada’s second-largest export behind energy: gold by itself surpassed the value of all car and truck exports late in 2024. Gold is only one example of rapid growth, as the fortunes of almost all mining industries have revived, including potash, copper, nickel, iron ore, and even coal.

Mining’s resurgence stands out as an example of Canada’s many struggling industries that positive market conditions can follow even the harshest of decades. The goal here is to profile its experience and draw on its lessons for other parts of the economy.

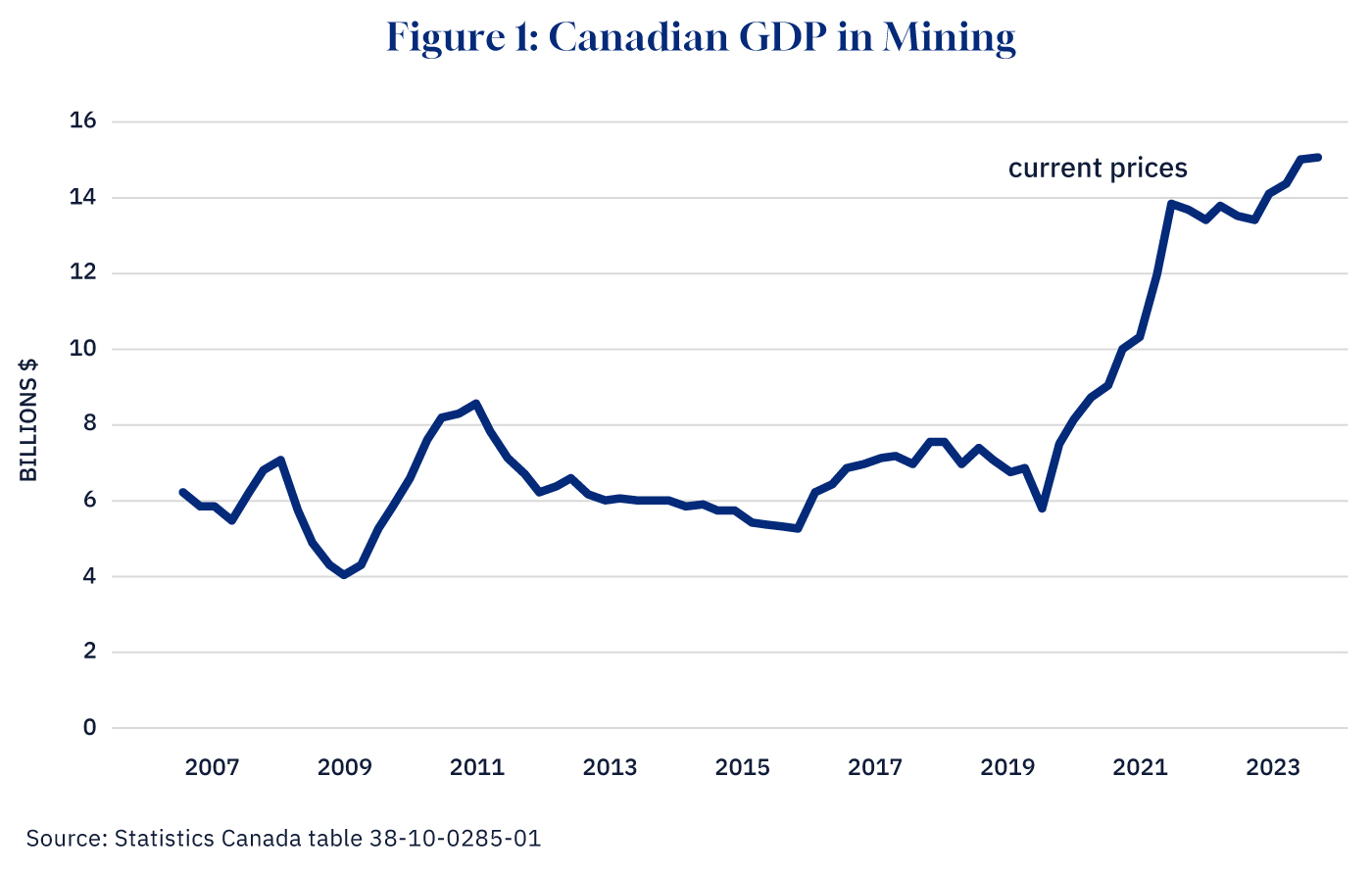

Record mining prices lift production

Nominal GDP generated by the mining industry has exploded in recent years (Figure 1).The data for nominal GDP in mining after 2007 come from Statistics Canada’s Satellite Account for Natural Resources. This definition of mining excludes coal and uranium, which are allocated to the energy sector. However, this has little impact on the trend of mining GDP in Figure 1. Income earned from mining extraction has almost doubled from its pre-pandemic high to $15.0 billion in the third quarter of 2024. This surge reflects consistently higher prices for mining products on world markets and solid gains in the volume of mining output. As a result, the share of mining in Canada’s overall GDP has risen from 0.9 percent at the turn of the century to 2.0 percent in 2024, a considerable increase since every 0.1 percentage point of GDP represents $3.1 billion.

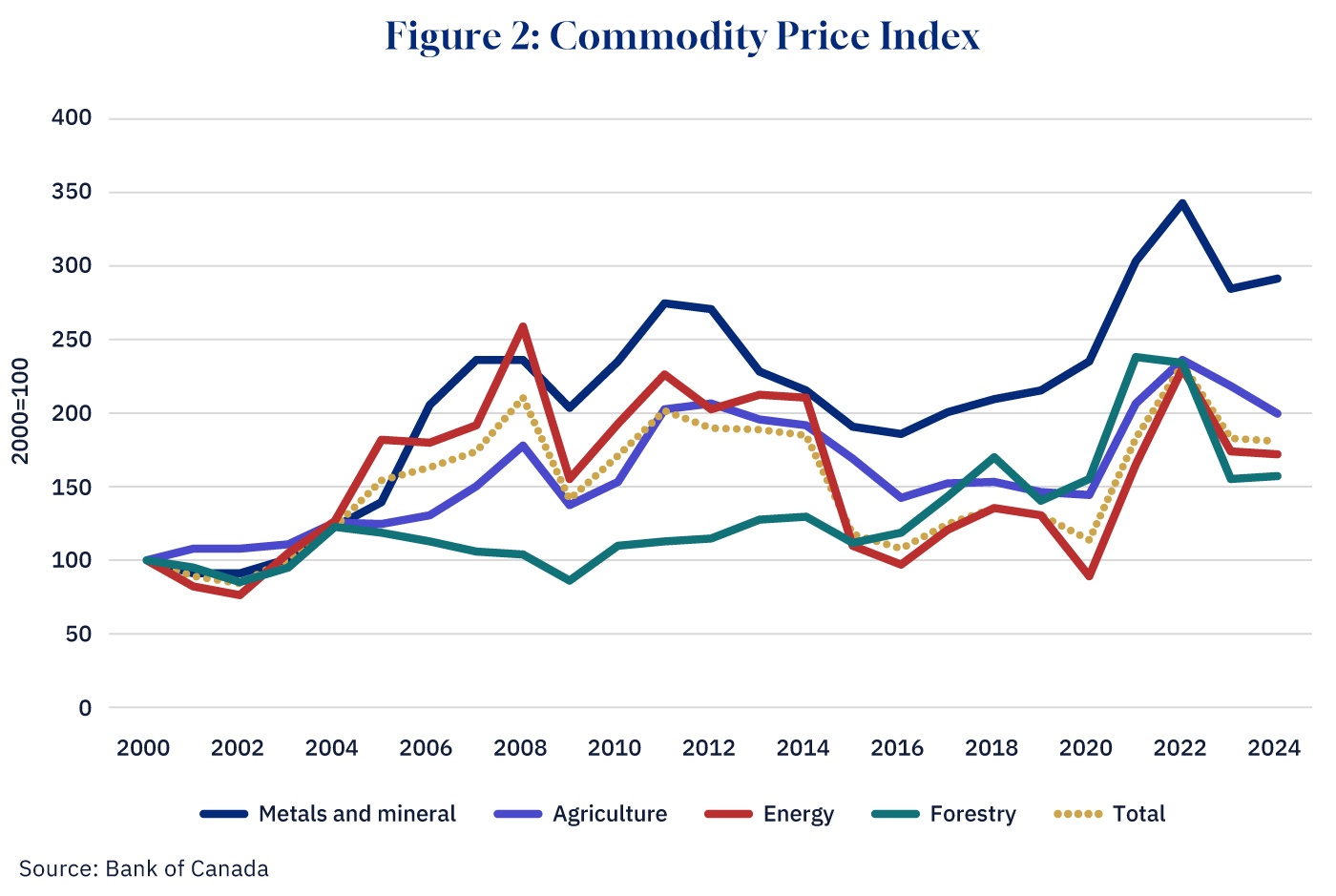

Mineral prices have risen faster than any other commodity since 2000, fuelling the boom in output, investment, and jobs (Figure 2). Energy prices get most of the public’s attention because the cost of gasoline and home heating has such a large impact on household budgets. However, prices for metals and minerals have increased 191 percent since 2000 versus a 72 percent gain for energy (also easily outdistancing increases for forestry and agricultural products). While energy prices might be more important to households, metal prices are a key barometer of the global economy: copper prices, for example, are such a key diagnostic tool of the health of industrial and housing demand that market participants refer to its price as “Doctor Copper.”

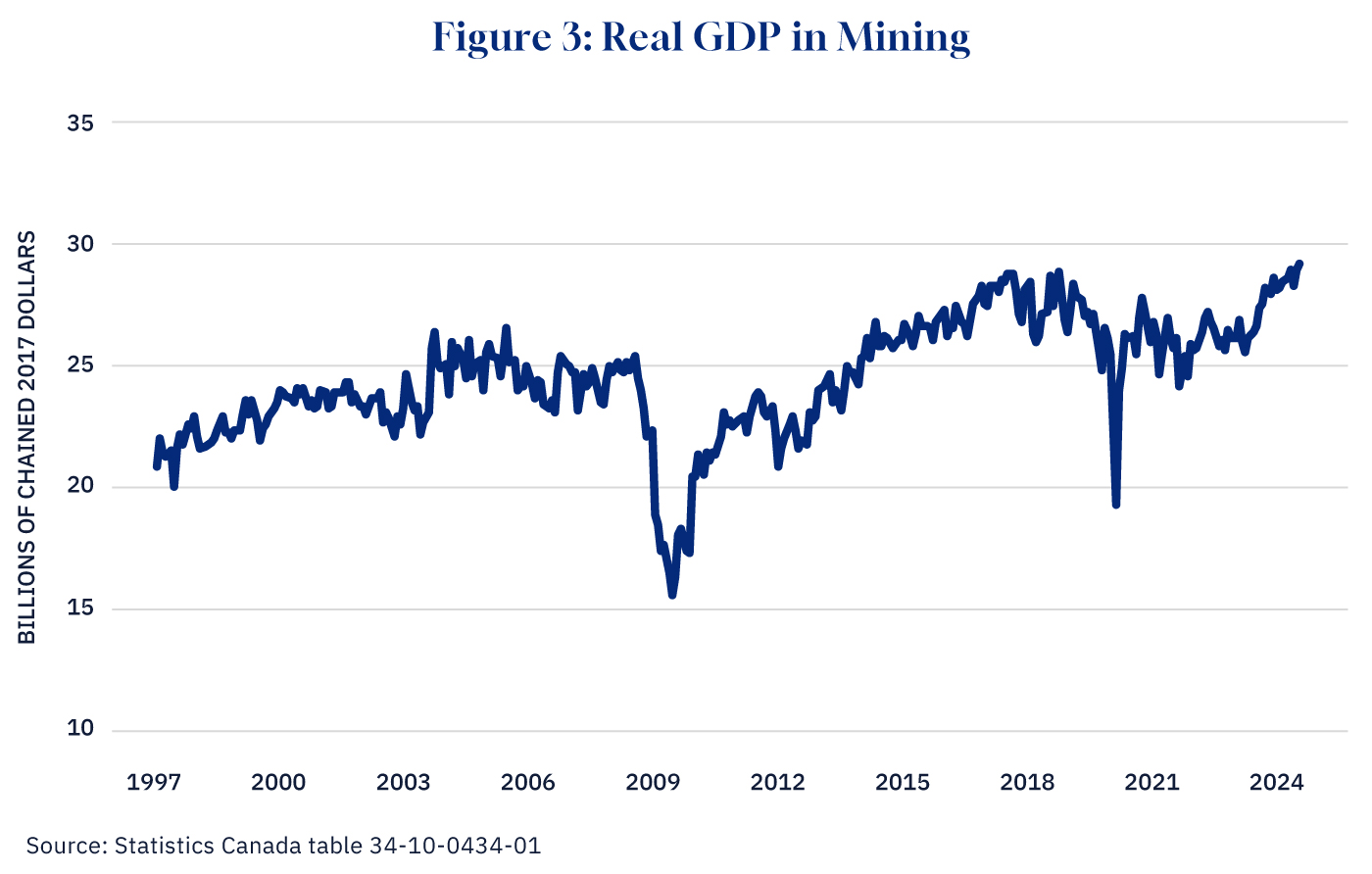

The volume of mining output has increased by one-third over the past two decades thanks to two periods of rapid growth (Figure 3). Production increased 15 percent between 2003 and 2008 as part of the so-called “Super Cycle” boom in commodity demand. After a bust associated with the Global Financial Crisis, output growth resumed (except during the COVID-19 pandemic), hitting a record high in 2024 that brought its total growth since 2009 to 88 percent. This growth rate puts mining in the vanguard of industry growth in Canada, which averaged only 39 percent over the same period.

Most provinces participated in the recent resurgence of mining production, with the exception of the Maritimes and Alberta.The Maritimes do not have significant commercial mineral deposits, while Alberta’s mining mostly consisted of coal, which was phased out from its electrical grid after 2016. Quebec and Newfoundland posted the fastest growth, with the value of mining output increasing four-fold after 2009.2021 is the latest year available from Statcan for current dollar GDP by province. As such, these provincial data omit the huge gains in mining income generated since 2021. However, the data are indicative of the importance of various mining industries to each province. All provincial data are from Statistics Canada Table 36-10-0402-01, GDP at basic prices, by industry and province. The expansion in Quebec was widespread, with notable gains for iron ore (which at $4.5 billion accounts for nearly half of its total GDP from mining) and, more recently, gold, copper, and nickel mines. Newfoundland’s increase was dominated by iron ore, which generates over 80 percent of the province’s mining income (the Voisey Bay nickel mine is well past its peak rate of production).

British Columbia, Ontario, and Saskatchewan all have more than doubled mining GDP since 2009. Most of Saskatchewan’s increase reflects a surge in potash mining. Ontario benefited from rising demand for gold and steady growth for its copper-nickel mines. Besides its own copper-nickel mines, British Columbia has significantly diversified its mining output in recent years with the discovery of new gold deposits in the so-called “Golden Triangle” located in the northwestern corner of the province and a notable rebound in demand for coal, which suddenly became its most valuable mineral with production worth $4.4 billion in 2021.

Excavators work at Atlantic Gold Corporation’s Touquoy open pit gold mine in Moose River Gold Mines, N.S. on Tuesday, June 6, 2017. Andrew Vaughan/The Canadian Press.

The recovery of mining justifies the confidence some provincial governments had that this industry could still be a source of potential growth, notably Quebec’s Plan Nord and Ontario’s support for developing the Ring of Fire projects. More recently, the federal government’s 2024 budget pledged to encourage mining investment by reducing regulatory barriers in recognition of the need to speed up development of strategic mineral deposits; as the budget ruefully noted, “it shouldn’t take over a decade to open a new mine.” The interest of governments in expanding mining operations is partly driven by their efforts to improve life in remote Indigenous communities, where mining often is the only realistic source of economic development. It is not surprising that provincial governments took the lead in identifying mining as a growth sector since mining has an important presence in almost all provinces (unlike several other high-profile industries such as autos, oil and gas, grains, aircraft, and hydroelectricity, which are concentrated in only a few provinces).

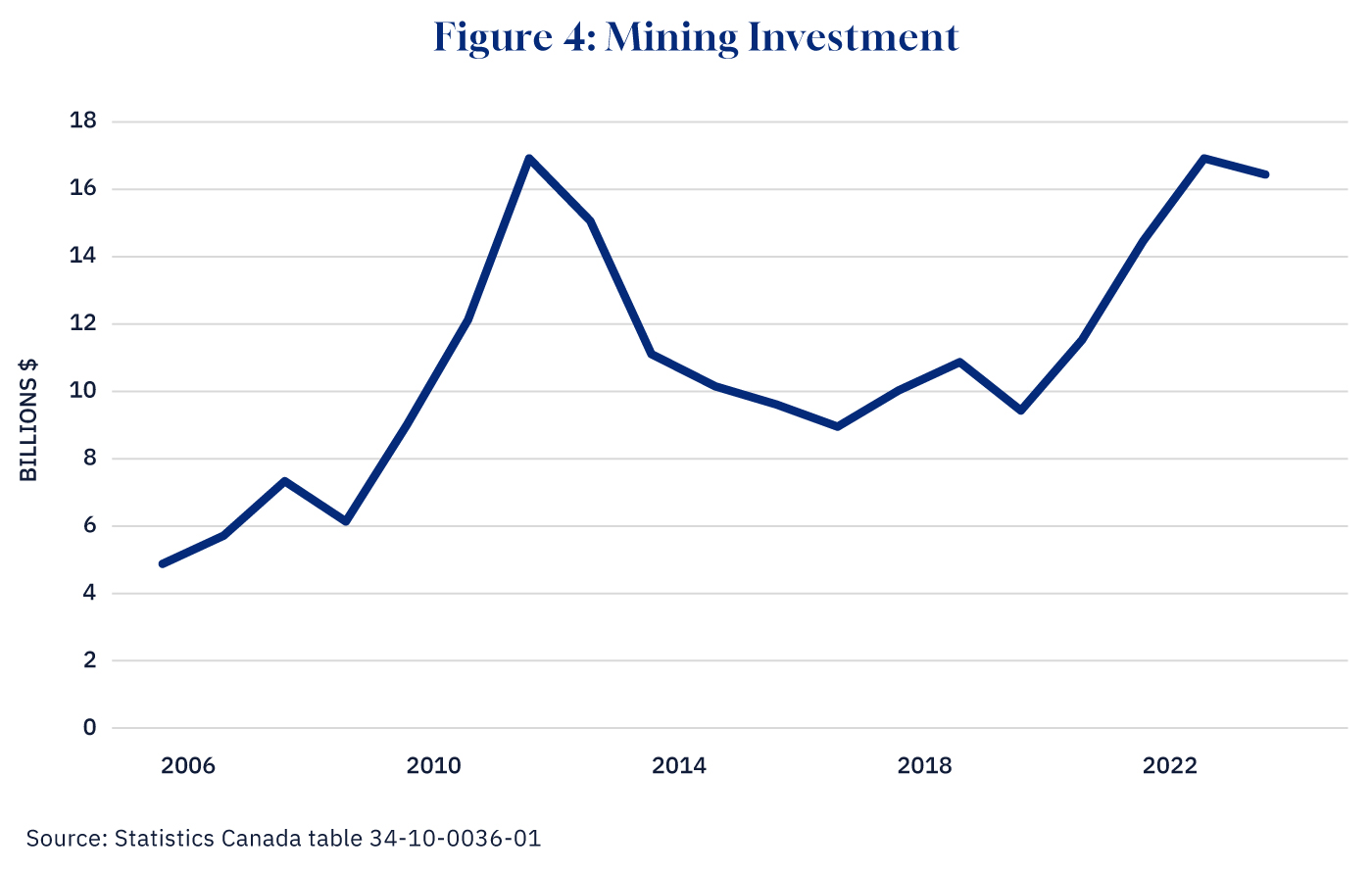

Investment in mining strengthens across the board

Mining investment has tripled since 2006, with virtually all industries participating in this boom. As with output, investment has risen in two distinct periods (Figure 4). Capital outlays first reached a peak in 2012 due to investments in metal ores such as gold and iron ore. Spending then subsided to more sustainable levels as several major projects were completed, and investor interest shifted from metal ores to non-metallic minerals. Investment then took off again in 2021, surpassing its previous record with $16.9 billion of spending in 2023. The strength of investment in a wide range of mining industries shows that firms expect demand to continue to trend higher for the foreseeable future.

While many mining industries have seen investment soar in recent years, gold and potash stand out with exceptional gains. Investment in gold totaled $19.0 billion over the last three years as high prices incentivized producers to search for new deposits. As recently as 2007, gold attracted less than $1 billion of investment. Gold accounted for the lion’s share (58.3 percent) of metal ore investment in Canada over the last three years, a considerable feat given the large investments in iron ore, nickel, and copper. Potash investment also mushroomed over the same period with outlays of $10.5 billion, although this strength was not as unprecedented as for gold (a similar boom sparked $11.7 billion of investment in potash between 2013 and 2015). The dominance of potash in non-metallic minerals is even greater than for gold in metal ores: between 2022 and 2024, capital outlays for potash of $10.5 billion represented 80.2 percent of all investment in non-metallic minerals in Canada.

While gold and potash have led the way, capital spending has been buoyant in almost all other mining industries in recent years. Nickel and copper mining attracted record investment of nearly $2 billion in each of the last three years.Data on copper and zinc mines are not publicly available due to confidentiality restrictions. Iron ore posted its best three years since 2011. Coal mining investment tripled from its lows a decade ago, belying its reputation as a dying industry in a world trying to wean itself from fossil fuels. While domestic consumption of coal in Canada has declined, overseas demand accelerated (mostly from Asian countries) and now accounts for nearly three-quarters of our coal sales.Statistics Canada. (2023) Coal for Christmas? A coal industry snapshot. Available online at: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/5211-coal-christmas-coal-industry-snapshot. Diamonds are one area where capital spending is waning, as the mines built in the early 2000s are exhausting their deposits and new sources have not yet been discovered.

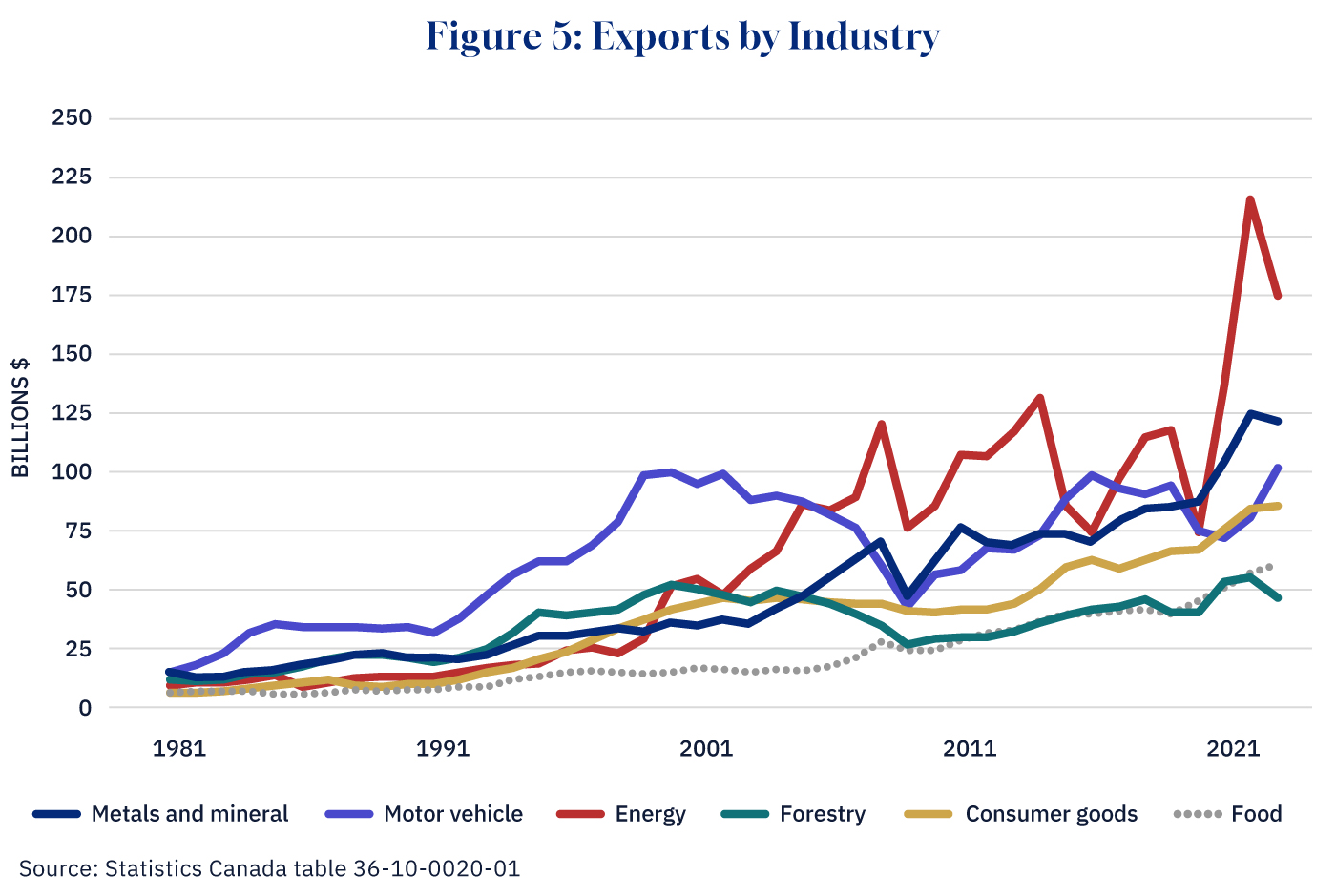

Mining is now Canada’s second-largest export

Mining exports more than tripled after 2003 to become Canada’s second leading export after energy (Figure 5). The surge reflects rising global demand for almost all metals and non-metallic minerals. This turnaround follows a decade of sluggish exports, with an average annual growth of only 4 percent in the 1990s that reduced mining to the second-lowest source of export earnings behind autos, forestry, energy, and consumer goods and ahead of only agricultural products. Exports shot up 20 percent a year during the commodity boom between 2003 and 2008. After nearly a decade of no growth in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, mining exports have experienced another growth spurt, averaging gains of 10 percent a year between 2016 and 2023. With exports far exceeding imports, metals and minerals generated a $39.3 billion trade surplus in 2023, the most of any sector except energy products.

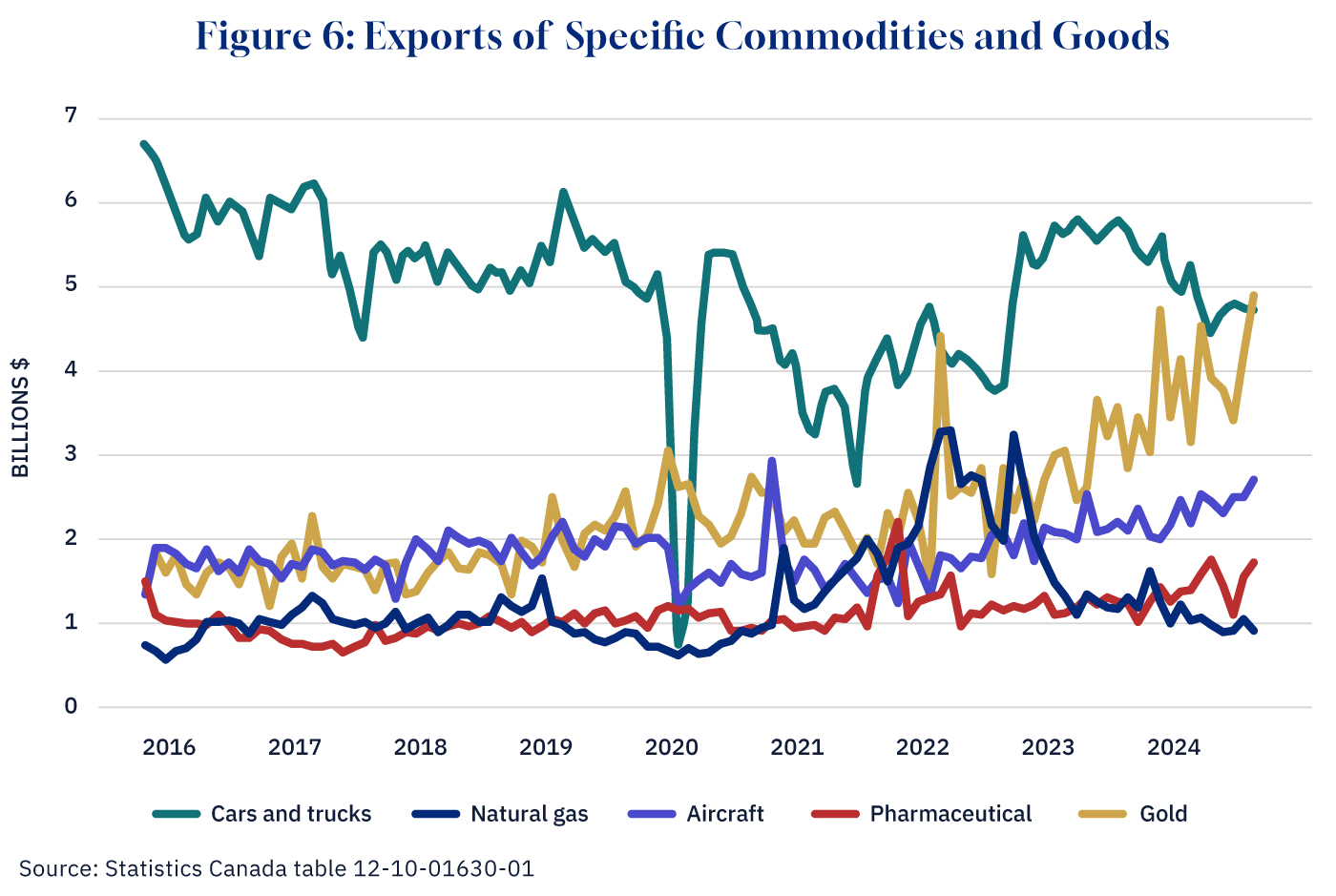

Gold exports spearheaded the most recent surge of mining exports, more than tripling since 2016 to a record $4.9 billion in November 2024 (Figure 6).While a small amount of gold exports reflects the re-export of imported gold that was refined in Canada, the surge of investment in gold mining and production documented throughout this paper shows that most gold exports are from domestic sources. Without any fanfare, gold has become Canada’s second-largest export, ahead of cars and trucks ($4.7 billion), industrial machinery ($4.2 billion), aircraft ($2.7 billion), pharmaceuticals ($1.7 billion), lumber, ($1.3 billion), and natural gas, ($0.9 billion) and behind only crude oil ($11.4 billion).

The strength in mining exports extends far beyond gold. Over the past decade, exports doubled for iron ore and potash, while aluminum and copper increased nearly 50 percent over the same period. Diamonds are the only major mineral where exports have declined as several mines in the Northwest Territories are nearing depletion.

Mining exports have a much more diversified export market outside the United States compared to energy and autos, Canada’s other two largest exports. In 2023, 44.1 percent of metal and mineral product exports went overseas.The data on exports by trading partner come from Statistics Canada Table 12-10-0171-01, Canadian international merchandise trade by country and by product section. This compares favourably with the almost exclusive reliance on the U.S. market for automotive products (93.4 percent of which go to the U.S.) and energy (80.7 percent). This is an important consideration as the Trump administration threatens across-the-board tariffs on Canadian exports.

Canada also exports its technical expertise in mining engineering and finance. It is said that many major mining sites around the world employ Canadian know-how of this industry. The Toronto Stock Exchange is the largest source of finance for mining projects in the world, reflecting decades of experience evaluating and financing mining projects. This expertise helps the mining industry generate large amounts of income from its work abroad, on top of the export income earned from shipments of mining commodities.

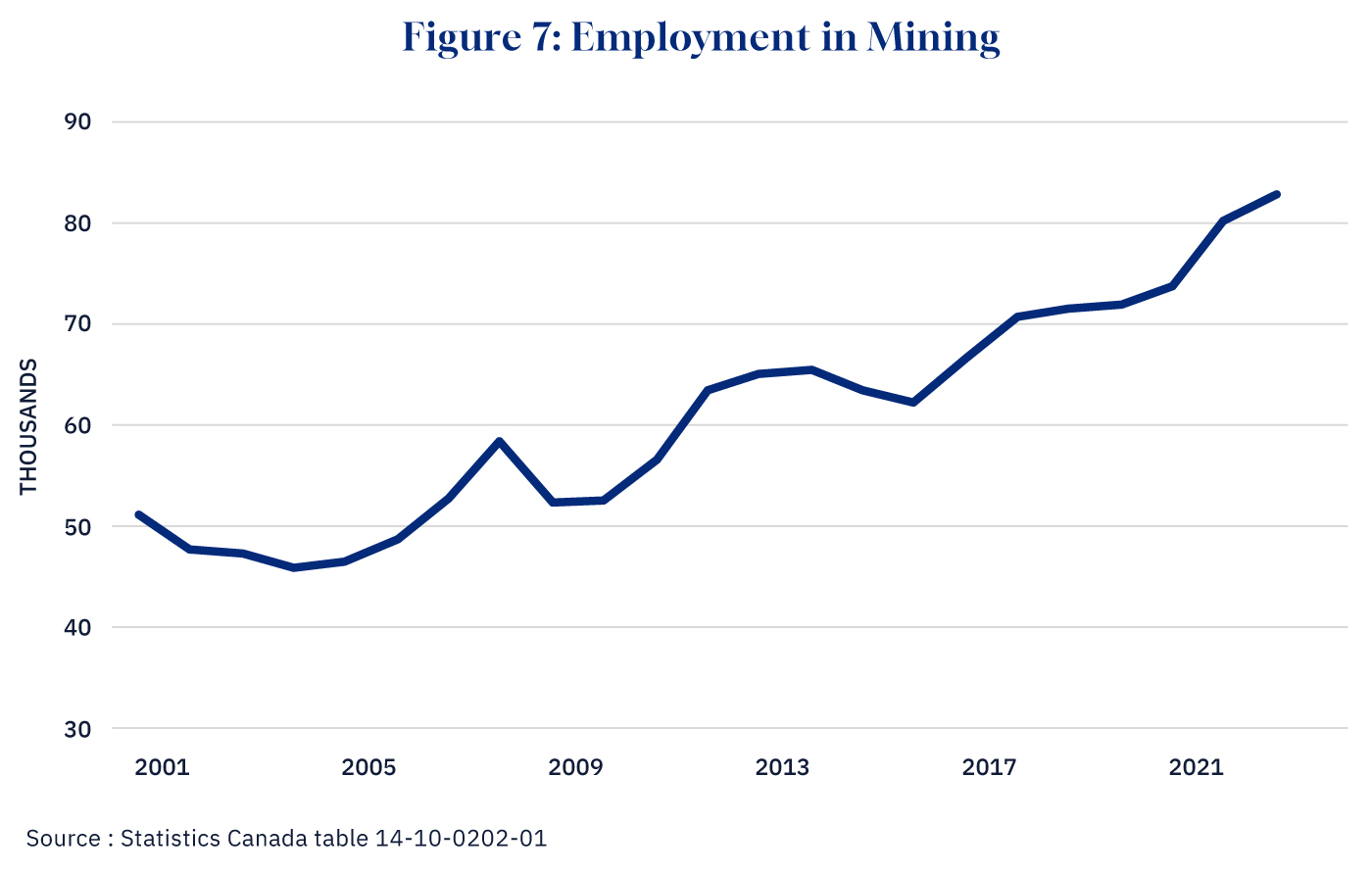

Mining employment

Mining directly employed 82,805 Canadians in 2023, nearly double its low of 45,986 in 2004 (Figure 7). The increase was concentrated in the two periods when exports grew rapidly. During the “Super Cycle” between 2003 and 2008, employment rose by an average of 4.7 percent a year. Following the bust associated with the Great Financial Crisis gripping much of the world, job growth slowed to an annual average of less than 1 percent a year until 2016. Since then, job growth has resumed at exactly the same annual average of 4.7 percent posted before 2008. This estimate of mining’s impact on jobs does not account for the spin-off effect on employment downstream in smelting and refining, the indirect impact on inputs sourced from other industries (including services such as engineering and finance), and the indirect impact on consumer spending from the high incomes earned in mining employment.

At 0.4 percent, mining directly accounts for a smaller part of employment in Canada than its 2.0 percent share of GDP. This partly reflects the capital-intensive nature of mining operations, which requires less labour. However, it also reflects that wages and salaries earned in mining are among the highest of any industry in Canada. The average weekly wage in mining was $2,091 in 2023, the third highest behind only oil and gas extraction and utilities.

Key takeaways

The resurgence of Canada’s mining sector underscores its critical role as a driver of economic growth, with its share of GDP doubling since the early 2000s and becoming the second-largest export sector behind energy. Fueled by record-high global prices, increased investment, and expanding output, the industry has experienced robust growth across various metals and minerals, including gold, potash, copper, and nickel. Provinces like Quebec and Newfoundland have seen notable gains, while investment in strategic minerals is receiving strong policy support to bolster economic development, particularly in remote and Indigenous communities. With employment nearly doubling since 2004 and mining exports diversifying beyond the U.S., the sector exemplifies Canada’s ability to compete globally and lead in areas like mining finance and engineering expertise, while exhibiting some insulation to fraying relations with the U.S. Mining’s success is a testament to the potential of resource industries to overcome past and present challenges and contribute significantly to Canada’s economic resilience and international standing.

However, while Canada has a strong geological potential, the policy environment must be right to maximize the economic benefits of mining. Canadian mining investment faces uncertainty from land disputes, burdensome regulations, and underdeveloped infrastructure that have manifested into delays of promising mineral deposits like Ontario’s Ring of Fire. As economic challenges with the U.S. rise, mining offers diverse export opportunities to bolster the Canadian economy. The time is now to get the policies right.